Panobinostat

HDAC inhibitors, orphan drug

cas 404950-80-7

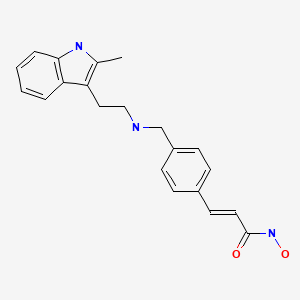

2E)-N-hydroxy-3-[4-({[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino}methyl)phenyl]acrylamide

N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide (alternatively, N-hydroxy-3-(4-{[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-ethylamino]-methyl}-phenyl)-acrylamide)

Molecular Formula: C21H23N3O2 Molecular Weight: 349.42622

- Faridak

- LBH 589

- LBH589

- Panobinostat

- UNII-9647FM7Y3Z

A hydroxamic acid analog histone deacetylase inhibitor from Novartis.

NOVARTIS, innovator

Histone deacetylase inhibitors

Is currently being examined in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, CML and breast cancer.

clinical trials click here phase 3

DRUG SUBSTANCE–LACTATE AS IN http://www.google.com/patents/US7989639 SEE EG 31

Panobinostat (LBH-589) is an experimental drug developed by Novartis for the treatment of various cancers. It is a hydroxamic acid[1] and acts as a non-selective histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDAC inhibitor).[2]

panobinostat

Panobinostat is a cinnamic hydroxamic acid analogue with potential antineoplastic activity. Panobinostat selectively inhibits histone deacetylase (HDAC), inducing hyperacetylation of core histone proteins, which may result in modulation of cell cycle protein expression, cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and apoptosis. In addition, this agent appears to modulate the expression of angiogenesis-related genes, such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1a) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thus impairing endothelial cell chemotaxis and invasion. HDAC is an enzyme that deacetylates chromatin histone proteins. Check for

As of August 2012, it is being tested against Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL)[3] and other types of malignant disease in Phase III clinical trials, against myelodysplastic syndromes, breast cancer and prostate cancer in Phase II trials, and against chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) in a Phase I trial.[4][5]

Panobinostat is a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor which was filed for approval in the U.S. in 2010 for the oral treatment of relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma in adult patients. The company is conducting phase II/III clinical trials for the oral treatment of multiple myeloma, chronic myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. Phase II trials are also in progress for the treatment of primary myelofibrosis, post-polycythemia Vera, post-essential thrombocytopenia, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, recurrent glioblastoma (GBM) and for the treatment of pancreatic cancer progressing on gemcitabine therapy. Additional trials are under way for the treatment of hematological neoplasms, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), malignant mesothelioma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, head and neck cancer and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Early clinical studies are also ongoing for the treatment of HER2 positive metastatic breast cancer. Additionally, phase II clinical trials are ongoing at Novartis as well as Neurological Surgery for the treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas as are phase I/II initiated for the treatment of acute graft versus host disease. The National Cancer Institute had been conducting early clinical trials for the treatment of metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma; however, these trials were terminated due to observed dose-limiting toxicity. In 2009, Novartis terminated its program to develop panobinostat for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. A program for the treatment of small cell lung cancer was terminated in 2012. Phase I clinical trials are ongoing for the treatment of metastatic and/or malignant melanoma and for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. The University of Virginia is conducting phase I clinical trials for the treatment of newly diagnosed and recurrent chordoma in combination with imatinib. Novartis is evaluating panobinostat for its potential to re-activate HIV transcription in latently infected CD4+ T-cells among HIV-infected patients on stable antiretroviral therapy.

Mechanistic evaluations revealed that panobinostat-mediated tumor suppression involved blocking cell-cycle progression and gene transcription induced by the interleukin IL-2 promoter, accompanied by an upregulation of p21, p53 and p57, and subsequent cell death resulted from the stimulation of caspase-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways and an increase in the mitochondrial outer membrane permeability. In 2007, the compound received orphan drug designation in the U.S. for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and in 2009 and 2010, orphan drug designation was received in the U.S. and the E.U., respectively, for the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. This designation was also assigned in 2012 in the U.S. and the E.U. for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the western world and during the last decades it has also become a rapidly increasing problem in developing countries. An estimated 80 million American adults (one in three) have one or more expressions of cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke. Mortality data show that CVD was the underlying cause of death in 35% of all deaths in 2005 in the United States, with the majority related to myocardial infarction, stroke, or complications thereof. The vast majority of patients suffering acute cardiovascular events have prior exposure to at least one major risk factor such as cigarette smoking, abnormal blood lipid levels, hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, and low-grade inflammation.

Pathophysiologically, the major events of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke are caused by a sudden arrest of nutritive blood supply due to a blood clot formation within the lumen of the arterial blood vessel. In most cases, formation of the thrombus is precipitated by rupture of a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque, which exposes chemical agents that activate platelets and the plasma coagulation system. The activated platelets form a platelet plug that is armed by coagulation-generated fibrin to form a biood clot that expands within the vessel lumen until it obstructs or blocks blood flow, which results in hypoxic tissue damage (so-called infarction). Thus, thrombotic cardiovascular events occur as a result of two distinct processes, i.e. a slowly progressing long-term vascular atherosclerosis of the vessel wall, on the one hand, and a sudden acute clot formation that rapidly causes flow arrest, on the other. This invention solely relates to the latter process.

Recently, inflammation has been recognized as an important risk factor for thrombotic events. Vascular inflammation is a characteristic feature of the atherosclerotic vessel wall, and inflammatory activity is a strong determinant of the susceptibility of the atherosclerotic plaque to rupture and initiate intravascular clotting. Also, autoimmune conditions with systemic inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and different forms of vasculitides, markedly increase the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke.

Traditional approaches to prevent and treat cardiovascular events are either targeted 1) to slow down the progression of the underlying atherosclerotic process, 2) to prevent clot formation in case of a plaque rupture, or 3) to direct removal of an acute thrombotic flow obstruction. In brief, antiatherosclerotic treatment aims at modulating the impact of general risk factors and includes dietary recommendations, weight loss, physical exercise, smoking cessation, cholesterol- and blood pressure treatment etc. Prevention of clot formation mainly relies on the use of antiplatelet drugs that inhibit platelet activation and/or aggregation, but also in some cases includes thromboembolic prevention with oral anticoagulants such as warfarin. Post-hoc treatment of acute atherothrombotic events requires either direct pharmacological lysis of the clot by thrombolytic agents such as recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator or percutaneous mechanical dilation of the obstructed vessel.

Despite the fact that multiple-target antiatherosclerotic therapy and clot prevention by antiplatelet agents have lowered the incidence of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, such events still remain a major population health problem. This shows that in patients with cardiovascular risk factors these prophylactic measures are insufficient to completely prevent the occurrence of atherothrombotic events.

Likewise, thrombotic conditions on the venous side of the circulation, as well as embolic complications thereof such as pulmonary embolism, still cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Venous thrombosis has a different clinical presentation and the relative importance of platelet activation versus plasma coagulation are somewhat different with an preponderance for the latter in venous thrombosis, However, despite these differences, the major underlying mechanisms that cause thrombotic vessel occlusions are similar to those operating on the arterial circulation. Although unrelated to atherosclerosis as such, the risk of venous thrombosis is related to general cardiovascular risk factors such as inflammation and metabolic aberrations.

Panobinostat can be synthesized as follows: Reduction of 2-methylindole-3-glyoxylamide (I) with LiAlH4 affords 2-methyltryptamine (II). 4-Formylcinnamic acid (III) is esterified with methanolic HCl, and the resulting aldehyde ester (IV) is reductively aminated with 2-methyltryptamine (II) in the presence of NaBH3CN (1) or NaBH4 (2) to give (V). The title hydroxamic acid is then obtained by treatment of ester (V) with aqueous hydroxylamine under basic conditions.

Panobinostat is currently being used in a Phase I/II clinical trial that aims at curing AIDS in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). In this technique panobinostat is used to drive the HI virus’s DNA out of the patient’s DNA, in the expectation that the patient’s immune system in combination with HAART will destroy it.[6][7]

panobinostat

panobinostat

Panobinostat has been found to synergistically act with sirolimus to kill pancreatic cancer cells in the laboratory in a Mayo Clinic study. In the study, investigators found that this combination destroyed up to 65 percent of cultured pancreatic tumor cells. The finding is significant because the three cell lines studied were all resistant to the effects of chemotherapy – as are many pancreatic tumors.[8]

Panobinostat has also been found to significantly increase in vitro the survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein levels in cells of patients suffering fromspinal muscular atrophy.[9]

Panobinostat was able to selectively target triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells by inducing hyperacetylation and cell cycle arrest at the G2-M DNA damage checkpoint; partially reversing the morphological changes characteristic of breast cancer cells.[10]

Panobinostat, along with other HDAC inhibitors, is also being studied for potential to induce virus HIV-1 expression in latently infected cells and disrupt latency. These resting cells are not recognized by the immune system as harboring the virus and do not respond to antiretroviral drugs.[11]

Panobinostat inhibits multiple histone deacetylase enzymes, a mechanism leading to apoptosis of malignant cells via multiple pathways.[1]

The compound N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide (alternatively, N-hydroxy-3-(4-{[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-ethylamino]-methyl}-phenyl)-acrylamide) has the formula

as described in WO 02/22577. Valuable pharmacological properties are attributed to this compound; thus, it can be used, for example, as a histone deacetylase inhibitor useful in therapy for diseases which respond to inhibition of histone deacetylase activity. WO 02/22577 does not disclose any specific salts or salt hydrates or solvates of N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide.

The compounds described above are often used in the form of a pharmaceutically acceptable salt. Pharmaceutically acceptable salts include, when appropriate, pharmaceutically acceptable base addition salts and acid addition salts, for example, metal salts, such as alkali and alkaline earth metal salts, ammonium salts, organic amine addition salts, and amino acid addition salts, and sulfonate salts. Acid addition salts include inorganic acid addition salts such as hydrochloride, sulfate and phosphate, and organic acid addition salts such as alkyl sulfonate, arylsulfonate, acetate, maleate, fumarate, tartrate, citrate and lactate. Examples of metal salts are alkali metal salts, such as lithium salt, sodium salt and potassium salt, alkaline earth metal salts such as magnesium salt and calcium salt, aluminum salt, and zinc salt. Examples of ammonium salts are ammonium salt and tetramethylammonium salt. Examples of organic amine addition salts are salts with morpholine and piperidine. Examples of amino acid addition salts are salts with glycine, phenylalanine, glutamic acid and lysine. Sulfonate salts include mesylate, tosylate and benzene sulfonic acid salts.

……………………………..

GENERAL METHOD OF SYNTHESIS

ADD YOUR METHYL AT RIGHT PLACE

As is evident to those skilled in the art, the many of the deacetylase inhibitor compounds of the present invention contain asymmetric carbon atoms. It should be understood, therefore, that the individual stereoisomers are contemplated as being included within the scope of this invention.

The hydroxamate compounds of the present invention can be produced by known organic synthesis methods. For example, the hydroxamate compounds can be produced by reacting methyl 4-formyl cinnamate with tryptamine and then converting the reactant to the hydroxamate compounds. As an example, methyl 4-formyl cinnamate 2, is prepared by acid catalyzed esterification of 4-formylcinnamic acid 3 (Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1995; 68:2355-2362). An alternate preparation of methyl 4-formyl cinnamate 2 is by a Pd- catalyzed coupling of methyl acrylate 4 with 4-bromobenzaldehyde 5.

CHO

Additional starting materials can be prepared from 4-carboxybenzaldehyde 6, and an exemplary method is illustrated for the preparation of aldehyde 9, shown below. The carboxylic acid in 4-carboxybenzaldehyde 6 can be protected as a silyl ester (e.g., the t- butyldimethylsilyl ester) by treatment with a silyl chloride (e.g., f-butyldimethylsilyl chloride) and a base (e.g. triethylamine) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., dichloromethane). The resulting silyl ester 7 can undergo an olefination reaction (e.g., a Horner-Emmons olefination) with a phosphonate ester (e.g., triethyl 2-phosphonopropionate) in the presence of a base (e.g., sodium hydride) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., tetrahydrofuran (THF)). Treatment of the resulting diester with acid (e.g., aqueous hydrochloric acid) results in the hydrolysis of the silyl ester providing acid 8. Selective reduction of the carboxylic acid of 8 using, for example, borane-dimethylsuflide complex in a solvent (e.g., THF) provides an intermediate alcohol. This intermediate alcohol could be oxidized to aldehyde 9 by a number of known methods, including, but not limited to, Swern oxidation, Dess-Martin periodinane oxidation, Moffatt oxidation and the like.

The aldehyde starting materials 2 or 9 can be reductively aminated to provide secondary or tertiary amines. This is illustrated by the reaction of methyl 4-formyl cinnamate 2 with tryptamine 10 using sodium triacetoxyborohydride (NaBH(OAc)3) as the reducing agent in dichloroethane (DCE) as solvent to provide amine 11. Other reducing agents can be used, e.g., sodium borohydride (NaBH ) and sodium cyanoborohydride (NaBH3CN), in other solvents or solvent mixtures in the presence or absence of acid catalysts (e.g., acetic acid and trifluoroacetic acid). Amine 11 can be converted directly to hydroxamic acid 12 by treatment with 50% aqueous hydroxylamine in a suitable solvent (e.g., THF in the presence of a base, e.g., NaOH). Other methods of hydroxamate formation are known and include reaction of an ester with hydroxylamine hydrochloride and a base (e.g., sodium hydroxide or sodium methoxide) in a suitable solvent or solvent mixture (e.g., methanol, ethanol or methanol/THF).

NOTE ….METHYL SUBSTITUENT ON 10 WILL GIVE YOU PANOBINOSTAT

![]()

……………………………….

Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2011 , vol. 54, 13 pg. 4694 – 4720

(E)-N-Hydroxy-3-(4-{[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-ethylamino]-methyl}-phenyl)-acrylamide

lactate

(34, panobinostat, LBH589)

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/jm2003552

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/suppl/10.1021/jm2003552/suppl_file/jm2003552_si_001.pdf

for str see above link

α-methyl-β-(β-bromoethyl)indole (29) was made according to method reported by Grandberg et al.(2. Grandberg, I. I.; Kost, A. N.; Terent’ev, A. P. Reactions of hydrazine derivatives. XVII. New synthesis of α-methyltryptophol. Zhurnal Obshchei Khimii 1957, 27, 3342–3345. )

The bromide 29 was converted to amine 30 by using similar method used by Sletzinger et al.(3. Sletzinger, M.; Ruyle, W. V.; Waiter, A. G. (Merck & Co., Inc.). Preparation of tryptamine

derivatives. U.S. Patent US 2,995,566, Aug 8, 1961.)

To a 500 mL flask, crude 2-methyltryptamine 30 (HPLC purity 75%, 1.74 g, 7.29 mmol) and 3-(4-

formyl-phenyl)-acrylic acid methyl ester 31 (HPLC purity 84%, 1.65 g, 7.28 mmol) were added,

followed by DCM (100 mL) and MeOH (30 mL). The clear solution was stirred at room temp for 30

min, then NaBH3CN (0.439 g, 6.99 mmol) was added in small portions. The reaction mixture was

stirred at room temp overnight. After removal of the solvents, the residue was diluted with DCM and

added saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution, extracted with DCM twice. The DCM layer was dried

and concentrated, and the resulting residue was purified by flash chromatography (silica, 0–10%

MeOH in DCM) to afford 33 as orange solid (1.52 g, 60%). LC–MS m/z 349.2 ([M + H]+). 33 was

converted to hydroxamic acid 34 according to procedure D (Experimental Section), and the freebase

34 was treated with 1 equiv of lactic acid in MeOH–water (7:3) to form lactic acid salt which was

further recrystallized in MeOH–EtOAc to afford the lactic acid salt of 34as pale yellow solid. LC–MS m/z 350.2 ([M + H − lactate]+).

= DELTA

1H NMR (DMSO-d6) 10.72 (s, 1H, NH), 7.54 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (td, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 7.8Hz, 2H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (td, J = 7.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 3.94(q, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, lactate CH), 3.92 (s, 2H), 2.88 and 2.81 (m, each, 4H, AB system, CH2CH2),2.31 (s, 3H), 1.21 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H).;

13C NMR (DMSO-d6) 176.7 (lactate C=O), 162.7, 139.0,

137.9, 135.2, 134.0, 132.1, 129.1, 128.1, 127.4, 119.9, 119.0, 118.1, 117.2, 110.4, 107.0, 66.0, 51.3,

48.5, 22.9, 20.7, 11.2.

![]()

…………………………………………..

PANOBINOSTAT DRUG SUBSTANCE SYNTHESIS AND DATA

http://www.google.com/patents/US7989639

A flow diagram for the synthesis of LBH589 lactate is provided in FIG. A. A nomenclature reference index of the intermediates is provided below in the Nomenclature Reference Index:

| Nomenclature reference index | |

| Compound | Chemical name |

| 1 | 4-Bromo-benzaldehyde |

| 2 | Methyl acrylate |

| 3 | (2E)-3-(formylphenyl)-2-propenoic acid, methyl ester |

| 4 | 3-[4-[[[2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3- |

| yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2- | |

| propenoic acid, methyl ester, monohydrochloride | |

| 5 | (2E)-N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3- |

| yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2-propenamide | |

| 6 | 2-hydroxypropanoic acid, compd. with 2(E)-N- |

| hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H- | |

| indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2-propenamide | |

| Z3a | 2-Methyl-1H-indole-3-ethanamine |

| Z3b | 5-Chloro-2-pentanone |

| Z3c | Phenylhydrazine |

The manufacture of LBH589 lactate (6) drug substance is via a convergent synthesis; the point of convergence is the condensation of indole-amine Z3a with aldehyde 3.

The synthesis of indole-amine Z3a involves reaction of 5-chloro-2 pentanone (Z3b) with phenylhydrazine (Z3c) in ethanol at reflux (variation of Fischer indole synthesis).

Product isolation is by an extractive work-up followed by crystallization. Preparation of aldehyde 3 is by palladium catalyzed vinylation (Heck-type reaction; Pd(OAc)2/P(o-Tol)3/Bu3N in refluxing CH3CN) of 4-bromo-benzyladehyde (1) with methyl acrylate (2) with product isolation via precipitation from dilute HCl solution. Intermediates Z3a and 3 are then condensed to an imine intermediate, which is reduced using sodium borohydride in methanol below 0° C. (reductive amination). The product indole-ester 4, isolated by precipitation from dilute HCl, is recrystallized from methanol/water, if necessary. The indole ester 4 is converted to crude LBH589 free base 5 via reaction with hydroxylamine and sodium hydroxide in water/methanol below 0° C. The crude LBH589 free base 5 is then purified by recrystallization from hot ethanol/water, if necessary. LBH589 free base 5 is treated with 85% aqueous racemic lactic acid and water at ambient temperature. After seeding, the mixture is heated to approximately 65° C., stirred at this temperature and slowly cooled to 45-50° C. The resulting slurry is filtered and washed with water and dried to afford LBH589 lactate (6).

If necessary the LBH589 lactate 6 may be recrystallised once again from water in the presence of 30 mol % racemic lactic acid. Finally the LBH589 lactate is delumped to give the drug substance. If a rework of the LBH589 lactate drug substance 6 is required, the LBH589 lactate salt is treated with sodium hydroxide in ethanol/water to liberate the LBH589 free base 5 followed by lactate salt formation and delumping as described above.

All starting materials, reagents and solvents used in the synthesis of LBH589 lactate are tested according to internal specifications or are purchased from established suppliers against a certificate of analysis.

EXAMPLE 7 Formation of Monohydrate Lactate Salt

About 40 to 50 mg of N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide free base was suspended in 1 ml of a solvent as listed in Table 7. A stoichiometric amount of lactic acid was subsequently added to the suspension. The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature and when a clear solution formed, stirring continued at 4° C. Solids were collected by filtration and analyzed by XRPD, TGA and 1H-NMR.

| TABLE 7 | |||||

| LOD, % | |||||

| Physical | Crystallinity | (Tdesolvation) | |||

| Solvent | T, ° C. | Appear. | and Form | Tdecomposit. | 1H-NMR |

| IPA | 4 | FFP | excellent | 4.3 (79.3) | — |

| HA | 156.3 | ||||

| Acetone | 4 | FFP | excellent | 4.5 (77.8) | 4.18 (Hbz) |

| HA | 149.5 | ||||

The salt forming reaction in isopropyl alcohol and acetone at 4° C. produced a stoichiometric (1:1) lactate salt, a monohydrate. The salt is crystalline, begins to dehydrate above 77° C., and decomposes above 150° C.

EXAMPLE 18 Formation of Anhydrous Lactate Salt

DL-lactic acid (4.0 g, 85% solution in water, corresponding to 3.4 g pure DL-lactic acid) is diluted with water (27.2 g), and the solution is heated to 90° C. (inner temperature) for 15 hours. The solution is allowed to cool down to room temperature and is used as lactic acid solution for the following salt formation step.

N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide free base (10.0 g) is placed in a 4-necked reaction flask with mechanical stirrer. Demineralized water (110.5 g) is added, and the suspension is heated to 65° C. (inner temperature) within 30 minutes. The DL-lactic acid solution is added to this suspension during 30 min at 65° C. During the addition of the lactate salt solution, the suspension converted into a solution. The addition funnel is rinsed with demineralized water (9.1 g), and the solution is stirred at 65° C. for an additional 30 minutes. The solution is cooled down to 45° C. (inner temperature) and seed crystals (10 mg N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate monohydrate) are added at this temperature. The suspension is cooled down to 33° C. and is stirred for additional 20 hours at this temperature. The suspension is re-heated to 65° C., stirred for 1 hour at this temperature and is cooled to 33° C. within 1 hour. After additional stirring for 3 hours at 33° C., the product is isolated by filtration, and the filter cake is washed with demineralized water (2×20 g). The wet filter-cake is dried in vacuo at 50° C. to obtain the anhydrous N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt as a crystalline product. The product is identical to the monohydrate salt (form HA) in HPLC and in 1H-NMR, with the exception of the integrals of water signals in the 1H-NMR spectra.

In additional salt formation experiments carried out according to the procedure described above, the product solution was filtered at 65° C. before cooling to 45° C., seeding and crystallization. In all cases, form A (anhydrate form) was obtained as product.

EXAMPLE 19 Formation of Anhydrous Lactate Salt

DL-lactic acid (2.0 g, 85% solution in water, corresponding to 1.7 g pure DL-lactic acid) is diluted with water (13.6 g), and the solution is heated to 90° C. (inner temperature) for 15 hours. The solution was allowed to cool down to room temperature and is used as lactic acid solution for the following salt formation step.

N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide free base (5.0 g) is placed in a 4-necked reaction flask with mechanical stirrer. Demineralized water (54.85 g) is added, and the suspension is heated to 48° C. (inner temperature) within 30 minutes. The DL-lactic acid solution is added to this suspension during 30 minutes at 48° C. A solution is formed. Seed crystals are added (as a suspension of 5 mg N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt, anhydrate form A, in 0.25 g of water) and stirring is continued for 2 additional hours at 48° C. The temperature is raised to 65° C. (inner temperature) within 30 minutes, and the suspension is stirred for additional 2.5 hours at this temperature. Then the temperature is cooled down to 48° C. within 2 hours, and stirring is continued at this temperature for additional 22 hours. The product is isolated by filtration and the filter cake is washed with demineralized water (2×10 g). The wet filter-cake is dried in vacuo at 50° C. to obtain anhydrous N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt (form A) as a crystalline product.

EXAMPLE 20 Conversion of Monohydrate Lactate Salt to Anhydrous Lactate Salt

DL-lactic acid (0.59 g, 85% solution in water, corresponding to 0.5 g pure DL-lactic acid) is diluted with water (4.1 g), and the solution is heated to 90° C. (inner temperature) for 15 hours. The solution is allowed to cool down to room temperature and is used as lactic acid solution for the following salt formation step.

10 g of N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt monohydrate is placed in a 4-necked reaction flask. Water (110.9 g) is added, followed by the addition of the lactic acid solution. The addition funnel of the lactic acid is rinsed with water (15.65 g). The suspension is heated to 82° C. (inner temperature) to obtain a solution. The solution is stirred for 15 minutes at 82° C. and is hot filtered into another reaction flask to obtain a clear solution. The temperature is cooled down to 50° C., and seed crystals are added (as a suspension of 10 mg N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt, anhydrate form, in 0.5 g of water). The temperature is cooled down to 33° C. and stirring is continued for additional 19 hours at this temperature. The formed suspension is heated again to 65° C. (inner temperature) within 45 minutes, stirred at 65° C. for 1 hour and cooled down to 33° C. within 1 hour. After stirring at 33° C. for additional 3 hours, the product is isolated by filtration and the wet filter cake is washed with water (50 g). The product is dried in vacuo at 50° C. to obtain crystalline anhydrous N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl) ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt (form A).

EXAMPLE 21 Formation of Anhydrous Lactate Salt

DL-lactic acid (8.0 g, 85% solution in water, corresponding to 6.8 g pure DL-lactic acid) was diluted with water (54.4 g), and the solution was heated to 90° C. (inner temperature) for 15 hours. The solution was allowed to cool down to room temperature and was used as lactic acid solution for the following salt formation step.

N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide (20 g) is placed in a 1 L glass reactor, and ethanol/water (209.4 g of a 1:1 w/w mixture) is added. The light yellow suspension is heated to 60° C. (inner temperature) within 30 minutes, and the lactic acid solution is added during 30 minutes at this temperature. The addition funnel is rinsed with water (10 g). The solution is cooled to 38° C. within 2 hours, and seed crystals (20 mg of N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt, anhydrate form) are added at 38° C. After stirring at 38° C. for additional 2 hours, the mixture is cooled down to 25° C. within 6 hours. Cooling is continued from 25° C. to 10° C. within 5 hours, from 10° C. to 5° C. within 4 hours and from 5° C. to 2° C. within 1 hour. The suspension is stirred for additional 2 hours at 2° C., and the product is isolated by filtration. The wet filter cake is washed with water (2×30 g), and the product is dried in vacuo at 45° C. to obtain crystalline anhydrous N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide lactate salt (form A).

EXAMPLE 28 Formation of Lactate Monohydrate Salt

3.67 g (10 mmol) of the free base monohydrate (N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl) ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide) and 75 ml of acetone were charged in a 250 ml 3-neck flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer and an addition funnel. To the stirred suspension were added dropwise 10 ml of 1 M lactic acid in water (10 mmol) dissolved in 20 ml acetone, affording a clear solution. Stirring continued at ambient and a white solid precipitated out after approximately 1 hour. The mixture was cooled in an ice bath and stirred for an additional hour. The white solid was recovered by filtration and washed once with cold acetone (15 ml). It was subsequently dried under vacuum to yield 3.94 g of the lactate monohydrate salt of N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[[2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]-2E-2-propenamide (86.2%).

![]()

References

- Revill, P; Mealy, N; Serradell, N; Bolos, J; Rosa, E (2007). “Panobinostat”. Drugs of the Future 32 (4): 315. doi:10.1358/dof.2007.032.04.1094476. ISSN 0377-8282.

- Table 3: Select epigenetic inhibitors in various stages of development from Mack, G. S. (2010). “To selectivity and beyond”. Nature Biotechnology 28 (12): 1259–1266.doi:10.1038/nbt.1724. PMID 21139608. edit

- ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00425555 Study of Oral LBH589 in Adult Patients With Refractory Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

- ClinicalTrials.gov: LBH-589

- Prince, HM; M Bishton (2009). “Panobinostat (LBH589): a novel pan-deacetylase inhibitor with activity in T cell lymphoma”. Hematology Meeting Reports (Parkville, Australia: Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and University of Melbourne) 3 (1): 33–38.

- Simons, J (27 April 2013). “Scientists on brink of HIV cure”. The Telegraph.

- ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01680094 Safety and Effect of The HDAC Inhibitor Panobinostat on HIV-1 Expression in Patients on Suppressive HAART (CLEAR)

- Mayo Clinic Researchers Formulate Treatment Combination Lethal To Pancreatic Cancer Cells

- Garbes, L; Riessland, M; Hölker, I; Heller, R; Hauke, J; Tränkle, Ch; Coras, R; Blümcke, I; Hahnen, E; Wirth, B (2009). “LBH589 induces up to 10-fold SMN protein levels by several independent mechanisms and is effective even in cells from SMA patients non-responsive to valproate”. Human Molecular Genetics 18 (19): 3645–3658. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp313.PMID 19584083.

- Tate, CR; Rhodes, LV; Segar, HC; Driver, JL; Pounder, FN; Burow, ME; and Collins-Burow, BM (2012). “Targeting triple-negative breast cancer cells with the histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat”. Breast Cancer Research 14 (3).

- TA Rasmussen, et al. Comparison of HDAC inhibitors in clinical development: Effect on HIV production in latently infected cells and T-cell activation. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 9:5, 1-9, May 2013.

- Drugs of the Future 32(4): 315-322 (2007)

- WO 2002022577…

- WO 2007146718

- WO 2013110280

- WO 2010009285

- WO 2010009280

- WO 2005013958

- WO 2004103358

- WO 2003048774…

- Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2011 , vol. 54, 13 pg. 4694 – 4720

-

11-26-2012Selective histone deacetylase 6 inhibitors bearing substituted urea linkers inhibit melanoma cell growth.Journal of medicinal chemistry

-

7-14-2011Discovery of (2E)-3-{2-butyl-1-[2-(diethylamino)ethyl]-1H-benzimidazol-5-yl}-N-hydroxyacrylamide (SB939), an orally active histone deacetylase inhibitor with a superior preclinical profile.Journal of medicinal chemistry

-

4-28-2011Discovery, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluation of spiropiperidine hydroxamic acid based derivatives as structurally novel histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors.Journal of medicinal chemistry

-

4-23-2009Identification and characterization of small molecule inhibitors of a class I histone deacetylase from Plasmodium falciparum.Journal of medicinal chemistry

-

1-1-2005The American Society of Hematology–46th Annual Meeting and Exposition. HDAC, Flt and farnesyl transferase inhibitors.IDrugs : the investigational drugs journal

-

8-3-2011PROCESS FOR MAKING SALTS OF N-HYDROXY-3-[4-[[[2-(2-METHYL-1H-INDOL-3-YL)ETHYL]AMINO]METHYL]PHENYL]-2E-2-PROPENAMIDE11-12-2010SALTS OF N-HYDROXY-3-[4-[[[2-(2-METHYL-1H-INDOL-3-YL)ETHYL]AMINO]METHYL]PHENYL]-2E-2-PROPENAMIDE7-16-2010Use of HDAC Inhibitors for the Treatment of Bone Destruction6-25-2010USE OF HDAC INHIBITORS FOR THE TREATMENT OF MYELOMA6-4-2010USE OF HDAC INHIBITORS FOR THE TREATMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL CANCERS12-11-2009PROCESS FOR MAKING N-HYDROXY-3-[4-[[[2-(2-METHYL-1H-INDOL-3-YL)ETHYL]AMINO]METHYL]PHENYL]-2E-2-PROPENAMIDE AND STARTING MATERIALS THEREFOR11-13-2009USE OF HDAC INHIBITORS FOR THE TREATMENT OF LYMPHOMAS10-23-2009Combination of a) N–4-(3-pyridyl)-2-pyrimidine-amine and b) a histone deacetylase inhibitor for the treatment of leukemia8-7-2009SALTS OF N-HYDROXY-3-[4-[[[2-(2-METHYL-1H-INDOL-3-YL)ETHYL]AMINO]METHYL]PHENYL]-2E-2-PROPENAMIDE1-9-2009Method of Use of Deacetylase Inhibitors

|

12-26-2008

|

Combination of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and Radiation

|

|

|

9-12-2008

|

Use of Hdac Inhibitors for the Treatment of Myeloma

|

|

|

7-25-2008

|

DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS

|

|

|

8-25-2006

|

Deacetylase inhibitors

|

|

|

6-28-2006

|

Deacetylase inhibitors

|

|

|

5-12-2006

|

Combination of a) n-{5-[4-(4-methyl-piperazino-methyl)-benzoylamido]2-methylphenyl}-4- (3-pyridyl)-2-pyrimidine-amine and b) a histone deacetylase inhibitor for the treatment of leukemia

|

|

|

12-22-2004

|

Deacetylase inhibitors

|

|

|

4-23-2003

|

Deacetylase inhibitors

|

| GB776693A | Title not available | |||

| GB891413A | Title not available | |||

| GB2185020A | Title not available | |||

| WO2002022577A2 | Aug 30, 2001 | Mar 21, 2002 | Kenneth Walter Bair | Hydroxamate derivatives useful as deacetylase inhibitors |

| WO2003016307A1 | Aug 6, 2002 | Aug 19, 1993 | Jolie Anne Bastian | β3 ADRENERGIC AGONISTS |

| WO2003039599A1 | Nov 5, 2002 | May 15, 2003 | Ying-Nan Pan Chen | Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor/histone deacetylase inhibitor combination |

| WO2005105740A2 | Apr 26, 2005 | Nov 10, 2005 | Serguei Fine | Preparation of tegaserod and tegaserod maleate |

| WO2006021397A1 | Aug 22, 2005 | Mar 2, 2006 | Recordati Ireland Ltd | Lercanidipine salts |

![]()

…………………………………..

extras

5. Mocetinostat (MGCD0103), including pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof. Balasubramanian et al., Cancer Letters 280: 211-221 (2009).

Mocetinostat, has the following chemical structure and name:

Vorinostat, including pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof. Marks et al., Nature Biotechnology 25, 84 to 90 (2007); Stenger, Community Oncology 4, 384-386 (2007).

Vorinostat has the following chemical structure and name:

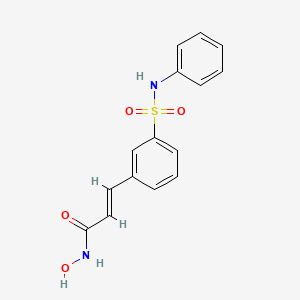

Belinostat (PXD-101 , PX-105684)

(2E)-3-[3-(anilinosulfonyl)phenyl]-N-hydroxyacrylamide

……………………………………………….

Dacinostat (LAQ-824, NVP-LAQ824,)

((E)-N-hydroxy-3-[4-[[2-hydroxyethyl-[2-(1 H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]phenyl]prop-2-enamide

Entinostat (MS-275, SNDX-275, MS-27-275)

4-(2-aminophenylcarbamoyl)benzylcarbamate

(a) The HDAC inhibitor Vorinostat™ or a salt, hydrate, or solvate thereof.

Vorinostat………………..

(b) The HDAC inhibitor Givinostat or a salt, hydrate, or solvate thereof.

Givinostat or a salt, hydrate, or solvate thereof.

BELINOSTAT

BELINOSTAT

CLAZOSENTAN

CLAZOSENTAN CLAZOSENTAN DI-NA SALT is discontinued

CLAZOSENTAN DI-NA SALT is discontinued

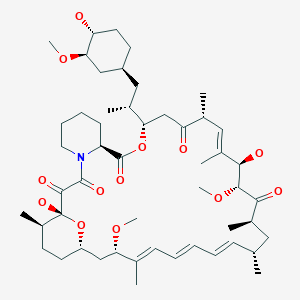

rapamycin

rapamycin SIROLIMUS

SIROLIMUS

SIROLIMUS

SIROLIMUS

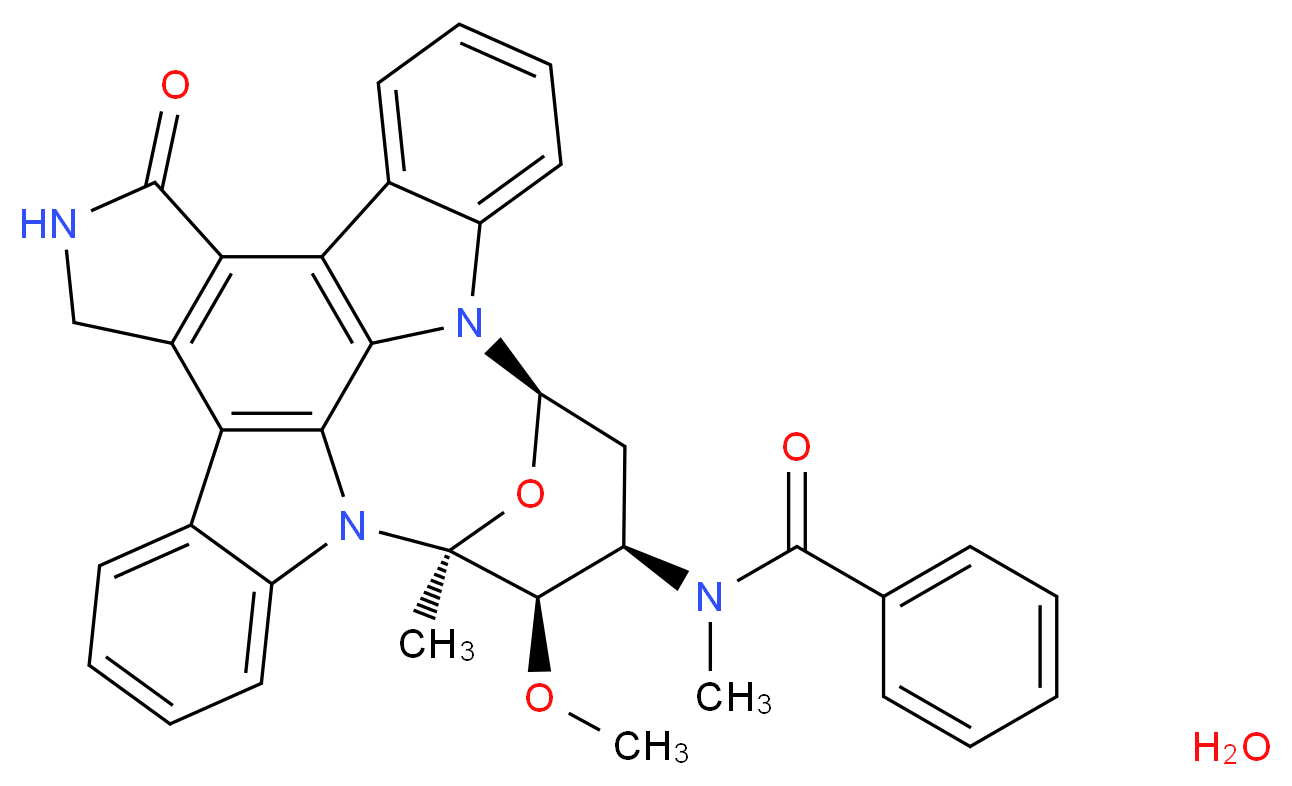

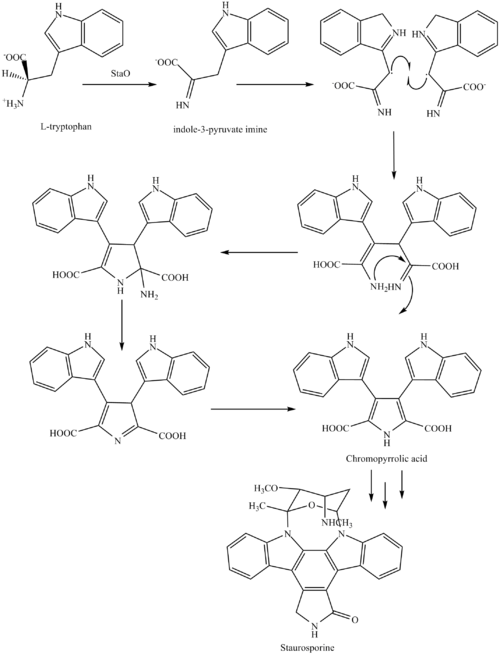

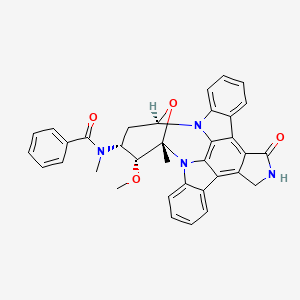

MIDOSTAURIN

MIDOSTAURIN MIDOSTAURIN

MIDOSTAURIN