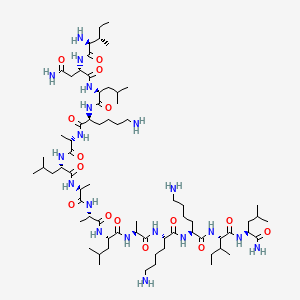

Mastoparan, Peptide (H-INLKALAALAKKIL-NH2)

IUPAC Condensed

H-Ile-Asn-Leu-Lys-Ala-Leu-Ala-Ala-Leu-Ala-Lys-Lys-xiIle-Leu-NH2

Sequence

INLKALAALAKKXL

HELM

PEPTIDE1{I.N.L.K.A.L.A.A.L.A.K.K.[*N[C@H](C(=O)*)C(C)CC |$_R1;;;;;_R2;;;;$|].L.[am]}$$$$

| Ile – Asn – Leu – Lys – Ala – Leu – Ala – Ala – Leu – Ala – Lys – Lys – Ile – Leu -NH2 |

| Mastoparan; Mast cell degranulating peptide (Vespula lewisii); NSC351907; CAS 72093-21-1; | |

| Molecular Formula: | C70H131N19O15 |

|---|---|

| Molecular Weight: | 1478.90744 g/mol |

- 18: PN: WO0181408 SEQID: 37 claimed protein

- 18: PN: WO2010069074 SEQID: 16 claimed protein

- L-Leucinamide, L-isoleucyl-L-asparaginyl-L-leucyl-L-lysyl-L-alanyl-L-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanyl-L-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-lysyl-L-lysyl-L-isoleucyl-

- Mastoparan 1

- NSC 351907

Description

| Physical State: | Solid |

| Derived from: | Synthetic. Originally isolated from wasp venom (Vespula lewisii) |

| Solubility: | Soluble in water (2.6 mg/ml), and 100% ethanol. |

| Storage: | Store at -20° C |

| Refractive Index: | n20D 1.53 |

| IC50: | Na+,K+-ATPase: IC50 = 7.5 µM |

Mastoparan is a peptide toxin from wasp venom. It has the chemical structure Ile-Asn-Leu-Lys-Ala-Leu-Ala-Ala-Leu-Ala-Lys-Lys-Ile-Leu-NH2.[2]

The net effect of mastoparan’s mode of action depends on cell type, but seemingly always involves exocytosis. In mast cells, this takes the form of histamine secretion, while in platelets and chromaffin cells release serotonin and catecholamines are found, respectively. Mastoparan activity in the anterior pituitary gland leads to prolactin release.

In the case of histamine secretion, the effect of mastoparan takes place via its interference with G protein activity. By stimulating theGTPase activity of certain subunits, mastoparan shortens the lifespan of active G protein. At the same time, it promotes dissociation of any bound GDP from the protein, enhancing GTP binding. In effect, the GTP turnover of G proteins is greatly increased by mastoparan. These properties of the toxin follow from the fact that it structurally resembles activated G protein receptors when placed in a phospholipid environment. The resultant G protein-mediated signaling cascade leads to intracellular IP3 release and the resultant influx of Ca2+.

In an experimental study conducted by Tsutomu Higashijima and his counterparts, mastoparan was compared to melittin, which is found in bee venom.[2] Mainly, the structure and reaction to phosphate was studied in each toxin. Using Circular Dichroism (CD), it was found that when mastoparan was exposed to methanol, an alpha helical form existed. It was concluded that strong intramolecular hydrogen bonding occurred. Also, two negative bands were present on the CD spectrum. In an aqueous environment, mastoparan took on a nonhelical, unordered form. In this case, only one negative band was observed on the CD spectrum. Adding phosphate buffer to mastoparan resulted in no effect.

Melittin produced a different conformational change than mastoparan. In an aqueous solution, melittin went from a nonhelical form to an alpha helix when phosphate was added to the solution. The binding of melittin to the membrane was believed to result fromelectrostatic interactions, not hydrophobic interactions.

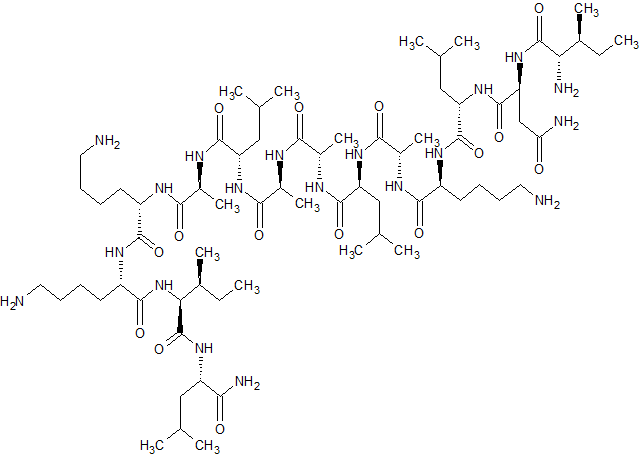

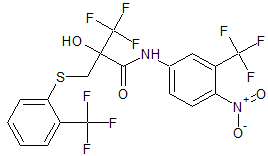

Infections caused by multidrug resistant bacteria are currently an important problem worldwide. Taking into account data recently published by the WHO, lower respiratory infections are the third cause of death in the world with around 3.2 million deaths per year, this number being higher compared to that related to AIDS or diabetes mellitus [1]. It is therefore important to solve this issue, although the perspectives for the future are not very optimistic. During the last 30 years an enormous increase has been observed of superbugs isolated in the clinical setting, especially from the group called ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp.) which show high resistance to all the antibacterial agents available [2]. We will focus on Acinetobacter baumannii, the pathogen colloquially called “iraquibacter” for its emergence in the Iraq war. It is a Gram-negative cocobacillus and normally affects people with a compromised immune system, such as patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) [3] and [4]. Together with Escherichia coliand P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii are the most common cause of nosocomial infections among Gram-negative bacilli. The options to treat infections caused by this pathogen are diminishing since pan-drug resistant strains (strains resistant to all the antibacterial agents) have been isolated in several hospitals [5]. The last option to treat these infections is colistin, which has been used in spite of its nephrotoxic effects [6]. The evolution of the resistance of A. baumannii clinical isolates has been established by comparing studies performed over different years, with the percentage of resistance to imipenem being 3% in 1993 increasing up to 70% in 2007. The same effect was observed with quinolones, with an increase from 30 to 97% over the same period of time[7]. In Spain the same evolution has been observed with carbapenems; in 2001 the percentage of resistance was around 45%, rising to more than 80% 10 years later [8]. Taking this scenario into account, there is an urgent need for new options to fight against this pathogen. One possible option is the use of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) [9],[10] and [11], and especially peptides isolated from a natural source [12]. One of the main drawbacks of using peptides as antimicrobial agents is the low stability or half-life in human serum due to the action of peptidases and proteases present in the human body[13], however there are several ways to increase their stability, such as using fluorinated peptides [14] and [15]. One way to circumvent this effect is to study the susceptible points of the peptide and try to enhance the stability by protecting the most protease labile amide bonds, while at the same time maintaining the activity of the original compound. Another point regarding the use of antimicrobial peptides is the mechanism of action. There are several mechanisms of action for the antimicrobial peptides, although the global positive charge of most of the peptides leads to a mechanism of action involving the membrane of the bacteria [16]. AMPs has the ability to defeat bacteria creating pores into the membrane [17], also acting as detergents [18], or by the carpet mechanism [19]. We have previously reported the activity of different peptides against colistin-susceptible and colistin-resistant A. baumannii clinical isolates, showing that mastoparan, a wasp generated peptide (H-INLKALAALAKKIL-NH2), has good in vitro activity against both colistin-susceptible and colistin-resistant A. baumannii [20]. Therefore, the aim of this manuscript was to study the stability of mastoparan and some of its analogues as well as elucidate the mechanism of action of these peptides.

Paper

Volume 101, 28 August 2015, Pages 34–40

Sequence-activity relationship, and mechanism of action of mastoparan analogues against extended-drug resistantAcinetobacter baumannii

- a ISGlobal, Barcelona Ctr. Int. Health Res. (CRESIB), Hospital Clínic – Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- b Biomedical Institute of Seville (IBiS), University Hospital Virgen del Rocío/CSIC/University of Seville, Seville, Spain

- c Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona), Barcelona, Spain

- d Department of Clinical Microbiology, CDB, Hospital Clinic, School of Medicine, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- e Department of Organic Chemistry, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0223523415300933

doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.06.016

Highlights

- •The most susceptible position of mastoparan is the peptide bond between isoleucine and asparagine.

- •The positive charge present in the N-terminal play an important role in the antimicrobial activity of the peptides.

- •Mastoparan and its enantiomer version exhibit a mechanism of action related to the membrane disruption of bacteria.

- •Three of the mastoparan analogues synthesized have good activity against highly resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

- •Two of the active analogues showed a significant increase in the human serum stability compared to mastoparan.

Abstract

The treatment of some infectious diseases can currently be very challenging since the spread of multi-, extended- or pan-resistant bacteria has considerably increased over time. On the other hand, the number of new antibiotics approved by the FDA has decreased drastically over the last 30 years. The main objective of this study was to investigate the activity of wasp peptides, specifically mastoparan and some of its derivatives against extended-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. We optimized the stability of mastoparan in human serum since the specie obtained after the action of the enzymes present in human serum is not active. Thus, 10 derivatives of mastoparan were synthetized. Mastoparan analogues (guanidilated at the N-terminal, enantiomeric version and mastoparan with an extra positive charge at the C-terminal) showed the same activity against Acinetobacter baumannii as the original peptide (2.7 μM) and maintained their stability to more than 24 h in the presence of human serum compared to the original compound. The mechanism of action of all the peptides was carried out using a leakage assay. It was shown that mastoparan and the abovementioned analogues were those that released more carboxyfluorescein. In addition, the effect of mastoparan and its enantiomer against A. baumannii was studied using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These results suggested that several analogues of mastoparan could be good candidates in the battle against highly resistant A. baumannii infections since they showed good activity and high stability.

References

- PDB: 2CZP; Todokoro Y, Yumen I, Fukushima K, Kang SW, Park JS, Kohno T, Wakamatsu K, Akutsu H, Fujiwara T (August 2006). “Structure of Tightly Membrane-Bound Mastoparan-X, a G-Protein-Activating Peptide, Determined by Solid-State NMR”. Biophys. J. 91 (4): 1368–79. doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.082735. PMC 1518647. PMID 16714348.

- Higashijima T, Uzu S, Nakajima T, Ross EM (May 1988). “Mastoparan, a peptide toxin from wasp venom, mimics receptors by activating GTP-binding regulatory proteins (G proteins)”. J. Biol. Chem. 263 (14): 6491–4. PMID 3129426.

Reference

-

- WHO’s First Global Report on Antibiotic Resistance Reveals Serious, Worldwide Threat to Public Health

- World Heal. Organ, Geneva (2014

-

- Bad bugs, No drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the infectious diseases Society of America

- Clin. Infect. Dis., 48 (2009), pp. 1–12

-

- An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

- Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 5 (2007), pp. 939–951

-

- The Acinetobacter baumannii oxymoron: commensal hospital dweller turned pan-drug-resistant menace

- Front. Microbiol., 23 (3) (2012), p. 148

-

- Therapeutic options for Acinetobacter baumannii infections: an update

- Expert. Opin. Pharmacother., 13 (2012), pp. 2319–2336

-

- Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria

- Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 25 (2005), pp. 11–25

-

- Therapeutic options for Acinetobacter baumannii infections

- Expert. Opin. Pharmacother., 9 (2008), pp. 587–599

-

- In vitro activity of 18 antimicrobial agents against clinical isolates of Acinetobacter spp. Multicenternational study GEIH-REIPI-Ab 2010

- Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin., 31 (2013), pp. 4–9

-

- Update of peptides with antibacterial activity

- Curr. Med. Chem., 19 (2012), pp. 6188–6198

-

- The human beta-defensin-3, an antibacterial peptide with multiple biological functions

- Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1758 (2006), pp. 1499–1512

-

- Structure, membrane orientation, mechanism, and function of pexiganan–a highly potent antimicrobial peptide designed from magainin

- Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1788 (2009), pp. 1680–1686

-

- Efficacy of six frog skin-derived antimicrobial peptides against colistin-resistant strains of theAcinetobacter baumannii group

- Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 39 (2012), pp. 317–320

-

- Antimicrobial activity and protease stability of peptides containing fluorinated amino acids

- J. Am. Chem. Soc., 129 (2007), pp. 15615–15622

-

- Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the infectious diseases Society of Ame

- Mol. Biosyst., 5 (2009), pp. 1143–1147

-

- Using fluorous amino acids to probe the effects of changing hydrophobicity on the physical and biological properties of the beta-hairpin antimicrobial peptide protegrin-1

- Biochemistry, 47 (2008), pp. 9243–9250

-

- Small cationic antimicrobial peptides delocalize peripheral membrane proteins

- Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 111 (2014), pp. E1409–E1418

-

- A. Lipid composition-dependent membrane fragmentation and pore-forming mechanisms of membrane disruption by pexiganan (MSI-78)

- Biochemistry, 52 (2013), pp. 3254–3263

-

- Detergent-type membrane fragmentation by MSI-78, MSI-367, MSI-594, and MSI-843 antimicrobial peptides and inhibition by cholesterol: a solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance study

- Biochemistry, 54 (2015), pp. 1897–1907

-

- Probing the “charge cluster mechanism” in amphipathic helical cationic antimicrobial peptides

- Biochemistry, 49 (2010), pp. 4076–4084

-

- In vitro activity of several antimicrobial peptides against colistin-susceptible and colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

- Clin. Microbiol. Infect., 18 (2012), pp. 383–387

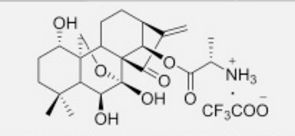

Patent IDDatePatent TitleUS20160672612016-03-10SERCA INHIBITOR AND CALMODULIN ANTAGONIST COMBINATION

| Mastoparan | |

|---|---|

Solution structure of mastoparan from Vespa simillima xanthoptera.[1]

|

|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | Mastoparan_2 |

| Pfam | PF08251 |

| InterPro | IPR013214 |

| TCDB | 1.C.32 |

| OPM superfamily | 160 |

| OPM protein | 2czp |

///////Peptide, Antimicrobial peptide, Mastoparan, Acinetobacter baumannii, NSC351907, 72093-21-1, NSC 351907

CCC(C)C(C(=O)NC(CC(=O)N)C(=O)NC(CC(C)C)C(=O)NC(CCCCN)C(=O)NC(C)C(=O)NC(CC(C)C)C(=O)NC(C)C(=O)NC(C)C(=O)NC(CC(C)C)C(=O)NC(C)C(=O)NC(CCCCN)C(=O)NC(CCCCN)C(=O)NC(C(C)CC)C(=O)NC(CC(C)C)C(=O)N)N