UCT’s H3D is a center of excellence for research and innovation with an already strong track record in malaria drug discovery. The vision of H3D is to be the leading organization for integrated drug discovery and development on the African continent.

ABOUT H3D

H3D is Africa’s first integrated drug discovery and development centre. The Centre was founded at the University of Cape Town in April 2011 and pioneers world-class drug discovery in Africa.

Our Vision

To be the leading organisation for integrated drug discovery and development from Africa, addressing global unmet medical needs.

Our Mission

To discover and develop innovative medicines for unmet medical needs on the African continent and beyond, by performing state-of-the-art research and development and bridging the gap between basic science and clinical studies.

We embrace partnerships with local and international governments, pharmaceutical companies, academia, and the private sector, as well as not-for-profit and philanthropic organisations, while training scientists to be world experts in the field.

The H3D collaboration with the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) focuses on delivering potential agents against malaria that will be affordable and safe to use. In line with the global aim to eradicate malaria, projects are pursued that not only eliminates blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infection, but also acts against liver stages and blocks transmission of the infection. The projects embrace multidisciplinary activities to optimise hit compounds from screening libraries through the drug discovery pipeline and deliver clinical candidates.

Merck Serono Announces Recipients of the Second Annual €1 Million Grant for Multiple Sclerosis Innovation

Merck signed a research agreement with the University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa, to co-develop a new R&D platform. It aims at identifying new lead programs for potential treatments against malaria, with the potential to expand it to other tropical diseases. It combines Merck’s R&D expertise and the drug discovery capabilities of the UCT Drug Discovery and Development Centre, H3D.

UCT’s H3D is a center of excellence for research and innovation with an already strong track record in malaria drug discovery. The vision of H3D is to be the leading organization for integrated drug discovery and development on the African continent. They say that working with partners like Merck is critical to build up a comprehensive pipeline to tackle malaria and related infectious diseases.

Journal Publications:

- Aminopyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines as potential inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Structure activity relationships and ADME characterization C. Soares de Melo, T-S. Feng, R. van der Westhuyzen, R.K. Gessner, L. Street, G. Morgans, D. Warner, A. Moosa, K. Naran, N. Lawrence, H. Boshoff, C. Barry, C. Harris, R. Gordon, K. Chibale. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 7240-7250.

- A Novel Pyrazolopyridine with in Vivo Activity in Plasmodium berghei- and Plasmodium falciparum- Infected Mouse Models from Structure−Activity Relationship Studies around the Core of Recently Identified Antimalarial Imidazopyridazines. C. Le Manach, T. Paquet, C. Brunschwig, M. Njoroge, Z. Han, D. Gonzàlez Cabrera, S. Bashyam, R. Dhinakaran, D. Taylor, J. Reader, M. Botha, A. Churchyard, S. Lauterbach, T. Coetzer, L-M. Birkholtz, S. Meister, E. Winzeler, D. Waterson, M. Witty, S. Wittlin, M-B. Jiménez-Díaz, M. Santos Martínez, S. Ferrer, I. Angulo-Barturen, L. Street, and K. Chibale, J. Med. Chem. 2015, XX, XXXX

- Structure−Activity Relationship Studies of Orally Active Antimalarial 2,4-Diamino-thienopyrimidines. D. Gonzàlez Cabrera, F. Douelle, C. Le Manach, Z. Han, T. Paquet, D. Taylor, M. Njoroge, N. Lawrence, L. Wiesner, D. Waterson, M. Witty, S. Wittlin, L. Street and K. Chibale. J Med Chem. 2015, 58, 7572-7579.

- Medicinal Chemistry Optimization of Antiplasmodial Imidazopyridazine Hits from High Throughput Screening of a SoftFocus Kinase Library: Part 2. Le Manach, T. Paquet, D. Gonzalez Cabrera, Y. Younis, D. Taylor, L. Wiesner, N. Lawrence, S. Schwager, D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, S. Wittlin, L. Street, and K. Chibale. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 8839−8848.

- Medicinal Chemistry Optimization of Antiplasmodial Imidazopyridazine Hits from High Throughput Screening of a SoftFocus Kinase Library: Part 1. Le Manach, D. González Cabrera, F. Douelle, A.T. Nchinda, Y. Younis, D. Taylor, L. Wiesner, K. White, E. Ryan, C. March, S. Duffy, V. Avery, D. Waterson, M. J. Witty, S. Wittlin; S. Charman, L. Street, and K. Chibale. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2789-2798.

- 2,4-Diamino-thienopyrimidines as Orally Active Antimalarial Agents. D. González Cabrera, C. Le Manach, F. Douelle, Y. Younis, T.-S. Feng, T. Paquet, A.T. Nchinda, L.J. Street, D. Taylor, C. de Kock, L. Wiesner, S. Duffy, K.L. White, K.M. Zabiulla, Y. Sambandan, S. Bashyam, D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, A. Charman, V.M. Avery, S. Wittlin, and K. Chibale. J. Med. Chem. 2014,57, 1014-1022.

- Effects of a domain-selective ACE inhibitor in a mouse model of chronic angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Burger, T.L. Reudelhuber, A. Mahajan, K. Chibale,E.D. Sturrock, R.M. Touyz. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 2014, 127(1), 57-63.

- Pharmacokinetic evaluation of lisinopril-tryptophan, a novel C-domain ACE inhibitor. Denti, S.K. Sharp, W.L. Kröger, S.L. Schwager, A. Mahajan, M. Njoroge, L. Gibhard, I. Smit, K. Chibale, L. Wiesner, E.D. Sturrock, N.H. Davies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.2014, 56, 113-119.

- Fragment-based design for the development of N-domain-selective angiotensin-1-converting enzyme inhibitors. R.G. Douglas, R.K. Sharma, G. Masuyer, L. Lubbe, I. Zamora, K.R. Acharya, K. Chibale, E.D. Sturrock. Sci. (Lond). 2014, 126(4),305-313.

- Fast in vitro methods to determine the speed of action and the stage-specificity of anti-malarials in Plasmodium falciparum. Le Manach, C. Scheurer, S. Sax, S. Schleiferböck, D. González Cabrera, Y. Younis, T. Paquet, L. Street, P.J. Smith, X. Ding, D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, D. Leroy, K. Chibale and S. Wittlin*. Malaria Journal, 2013, 12, 424.

- Structure-Activity-Relationship Studies Around the 2-Amino Group and Pyridine Core of Antimalarial 3,5-Diarylaminopyridines Lead to a Novel Series of Pyrazine Analogues with Oral in vivo Activity. Y. Younis, F. Douelle, González Cabrera, C. Le Manach, A.T. Nchinda, T. Paquet, L.J. Street, K.L. White, K. M. Zabiulla, J.T. Joseph, S. Bashyam, D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, S. Wittlin, S.A. Charman, and K. Chibale* J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 8860−8871.

- Cell-based Medicinal Chemistry Optimization of High Throughput Screening (HTS) Hits for Orally Active Antimalarials-Part 2: Hits from SoftFocus Kinase and other Libraries. Y. Younis, L. J. Street, D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, and K. Chibale. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7750−7754.

- Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of Orally active Antimalarial 3,5-Substituted 2-Aminopyridines. D. González Cabrera, F. Douelle, Y. Younis, T.-S. Feng, C. Le Manach, A.T. Nchinda, L.J. Street, C. Scheurer, J. Kamber, K. White, O. Montagnat, E. Ryan, K. Katneni, K.M. Zabiulla, J. Joseph, S. Bashyam, D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, S. Charman, S. Wittlin, and K. Chibale* J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 11022– 11030.

- 3,5-Diaryl-2-aminopyridines as a Novel Class of Orally Active Antimalarials Demonstrating Single Dose Cure in Mice and Clinical Candidate Potential. Y. Younis, F. Douelle, T.-S. Feng, D. González Cabrera, C. Le Manach, A.T. Nchinda, S. Duffy, K.L. White, M. Shackleford, J. Morizzi, J. Mannila, K. Katneni, R. Bhamidipati, K. M. Zabiulla, J.T. Joseph, S. Bashyam, D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, D. Hardick, S. Wittlin, V. Avery, S.A. Charman, and K. Chibale*. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3479−3487.

- Novel Orally Active Antimalarial Thiazoles. D. González Cabrera, F. Douelle, T.-S Feng, A.T. Nchinda, Y. Younis, K.L. White, Wu,E. Ryan, J.N. Burrows,D. Waterson, M.J. Witty,S. Wittlin,S.A. Charman and K. Chibale. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7713–7719.

- Synthesis and molecular modeling of a lisinopril-tryptophan analogue inhibitor of angiotensin I-converting enzyme. A.T. Nchinda, K. Chibale, P. Redelinghuys and E.D. Sturrock. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16(17), 4616-4619.

Patents

- Anti-Malarial Agents. Y. Younis, K. Chibale, M.J. Witty, D. Waterson. (2016) US9266842 B2.

- New Anti-Malarial Agents. D. Waterson, M.J. Witty, K. Chibale, L. Street, D. González Cabrera, T. Paquet. EP patent application (2015), No. 15 176 514.6.

- Preparation of aminopyrazine compounds as antimalarial agents for treatment of malaria. Y. Younis, K. Chibale, M.J. Witty, D. Waterson. PCT Int Appl. (2013), WO 2013121387 A1 20130822.

- Preparation of peptides as angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. E.D. Sturrock, A.T. Nchinda, K. Chibale. PCT Int. ppl. (2006), WO 2006126087 A2 20061130.

- Preparation of peptides as angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, E.D. Sturrock, A.T. Nchinda, K. Chibale. PCT Int. ppl. (2006), WO 2006126086 A2 20061130.

Head Office, Medicinal Chemistry Unit

Physical Address:

Department of Chemistry

7.32 H3D Lab Suite, PD Hahn Building, Level 7

North Lane off Ring Road

Upper Campus, University of Cape Town

Rondebosch, 7700, South Africa

T | 021 650 5495

F | 021 650 5195

Postal Address:

University of Cape Town

Private Bag X3

Rondebosch 7701

South Africa

//////H3D, Africa, integrated drug discovery and development centre, University of Cape Town

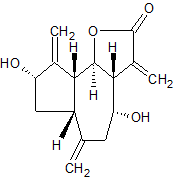

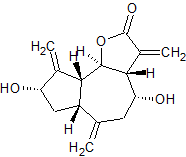

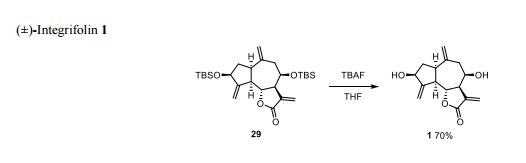

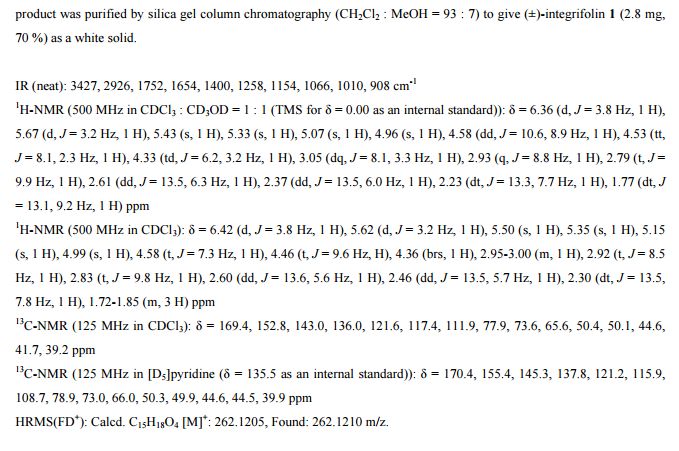

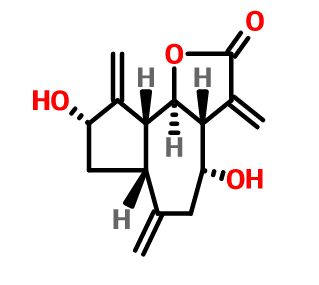

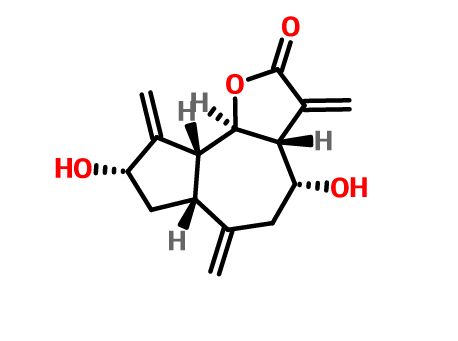

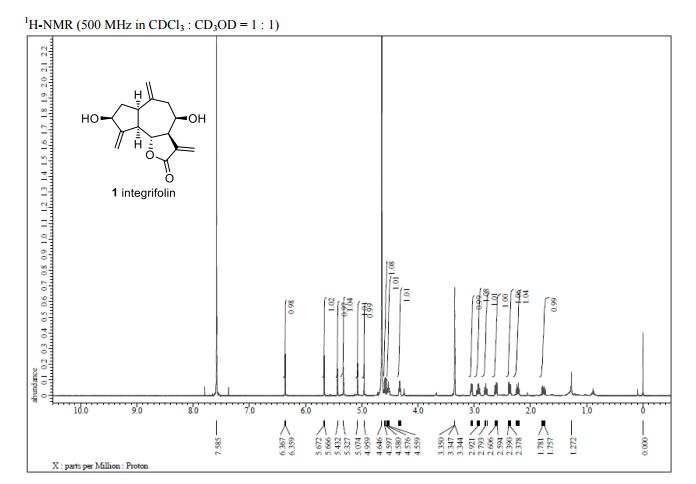

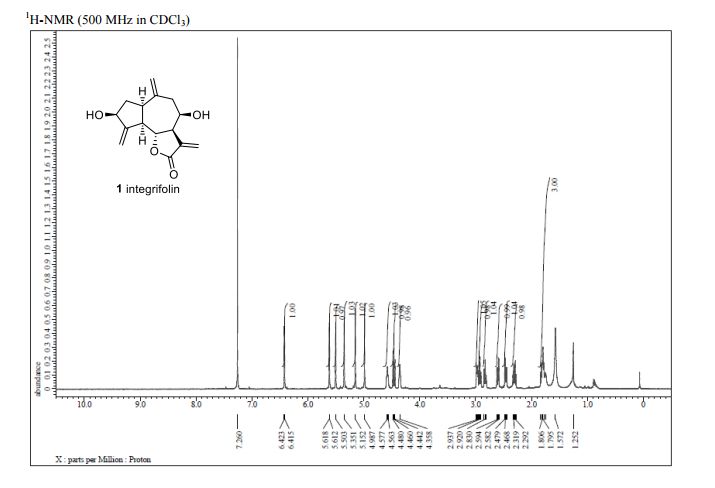

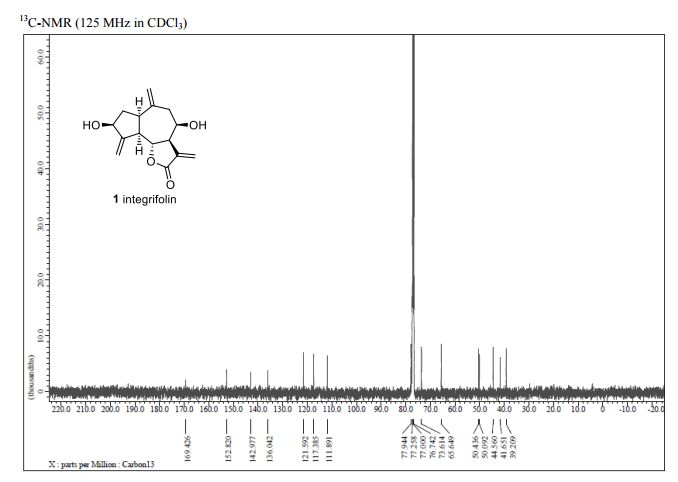

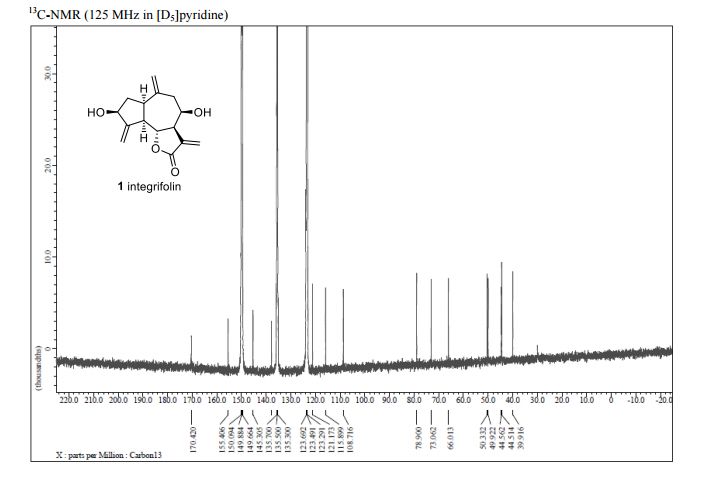

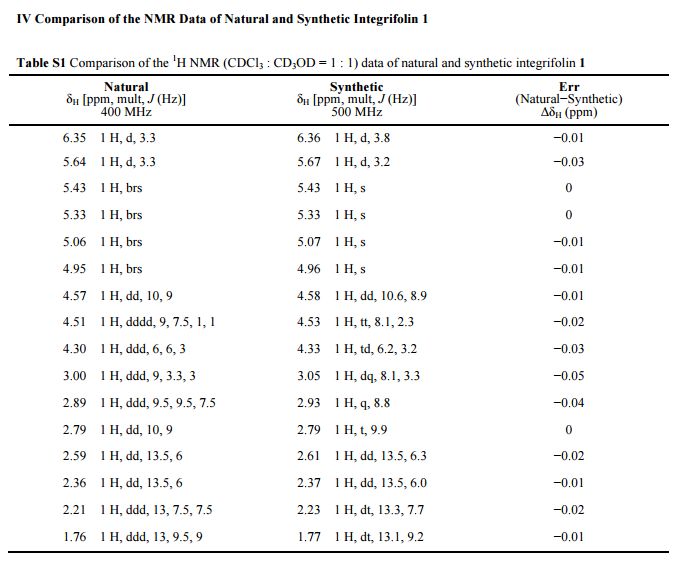

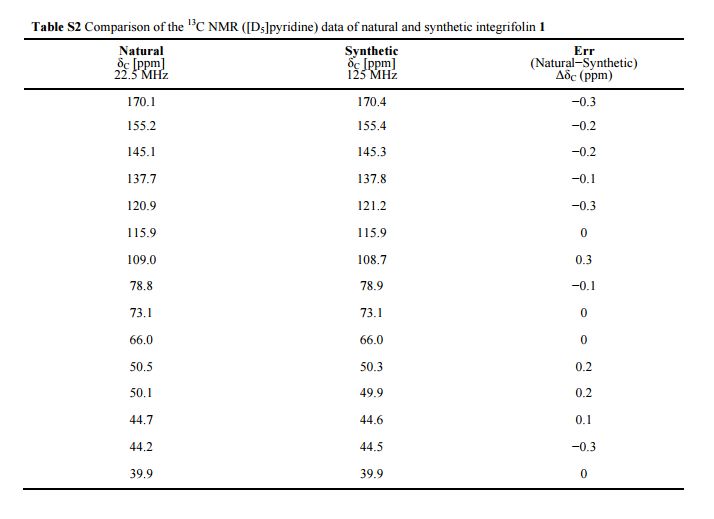

Integrifolin

Integrifolin

Journal title :

Journal title :